Building Inclusive Communities Through Safe Bike Access

What does unlocking a core nostalgic memory look like for you? For many of us, biking with our best friends through the streets of our childhood neighborhoods, keeping pace with one another, and finding the next adventure comes to mind. What happens when those carefree days dissipate and the next thing you know, your three-mile commute home turns into 40 minutes filled with honking horns and traffic jams beyond your line of sight? What if we took back our biking and made our commutes enjoyable again?

Safe Bike Access in Equitable Communities

Transportation infrastructure directly impacts how a community functions. All modes of transportation need to be accessible, safe, and equitable for every community member. When creating biking networks that are inclusive of all ages and abilities, the 8 to 80 rule is kept in mind throughout the design phase – meaning that biking networks need to work great for an 8-year-old and an 80-year-old, which comprises a large percent of the population.

Another large part of the population are community members who bike at slower speeds when commuting. To keep these cyclists safe and comfortable, they prefer sidewalks, bike lanes, and roads to be separated from each other. Confident cyclists, who only comprise of 5-10 percent of the population (FHWA Bikeway Selection Guide, 2019), are comfortable using shared roads. When creating bike facilities, designs should be inclusive of all levels of bicyclists, not just the small percentage of fast travelers. Building equitable active transportation means people have options and aren’t restricted to one travel mode.

Biking Benefits Us All – Here’s How

Getting people back on their bikes and into the world creates many benefits to an individual and their community. At the most basic level, exercising in any fashion throughout the day, even if biking casually, is crucial to overall public health and wellness. After all, just 11 minutes of daily aerobic exercise, such as cycling, walking, dancing, or jogging, can lower risk of disease and premature death, states CNN, and that’s worth every minute.

When a roadway is transformed to safely accommodate bikes, individuals are more inclined to stop at stores along the way. It is much easier to park a bike than to spend half an hour finding a parking spot downtown, that might not even be free — at which point, you might go home feeling defeated and skip downtown all together. Biking allows cyclists to invest in their communities by spending locally versus spending money on parking, gas, and vehicle maintenance. When biking networks are improved in high traffic areas, the economic impact can shift in a positive direction.

Socially, biking is a great way to bond with fellow cyclists. On bike trails or roadway lanes that allow side by side biking, cyclists can ride together to and from their commute. This allows for more camaraderie and relationship building rather than if two people were traveling separately by car to the same destination. Using active transportation in open public spaces facilitates a level of vulnerability that allows for more meaningful human interaction.

In addition to the personal benefits of biking, there is an even greater impact on the environment around us. “Choosing a bike over a car just once a day reduces the average person’s carbon emissions from transportation by 67 percent,” mentions a UCLA article. If cyclists make up a greater proportion of the total transportation and in turn, reduce the number of cars on the road, the benefits are compounded by creating less congestion and less emissions for the remaining vehicles. This small change creates cleaner air for everyone.

When we consider the numerous social, health, and financial benefits of bikeable communities, we begin to understand the obvious need for incorporating safe active transportation into our community planning efforts.

Safe Bike Access in Transportation Planning

There are many safety methods to consider when designing bikeways. The first is to determine if the bikeway will serve better as a bike trail (or greenway) or a cycle track (alongside a roadway corridor). Bike trails have their own right-of-way; these trails get cyclists into nature, which improves the biking and walking experience.

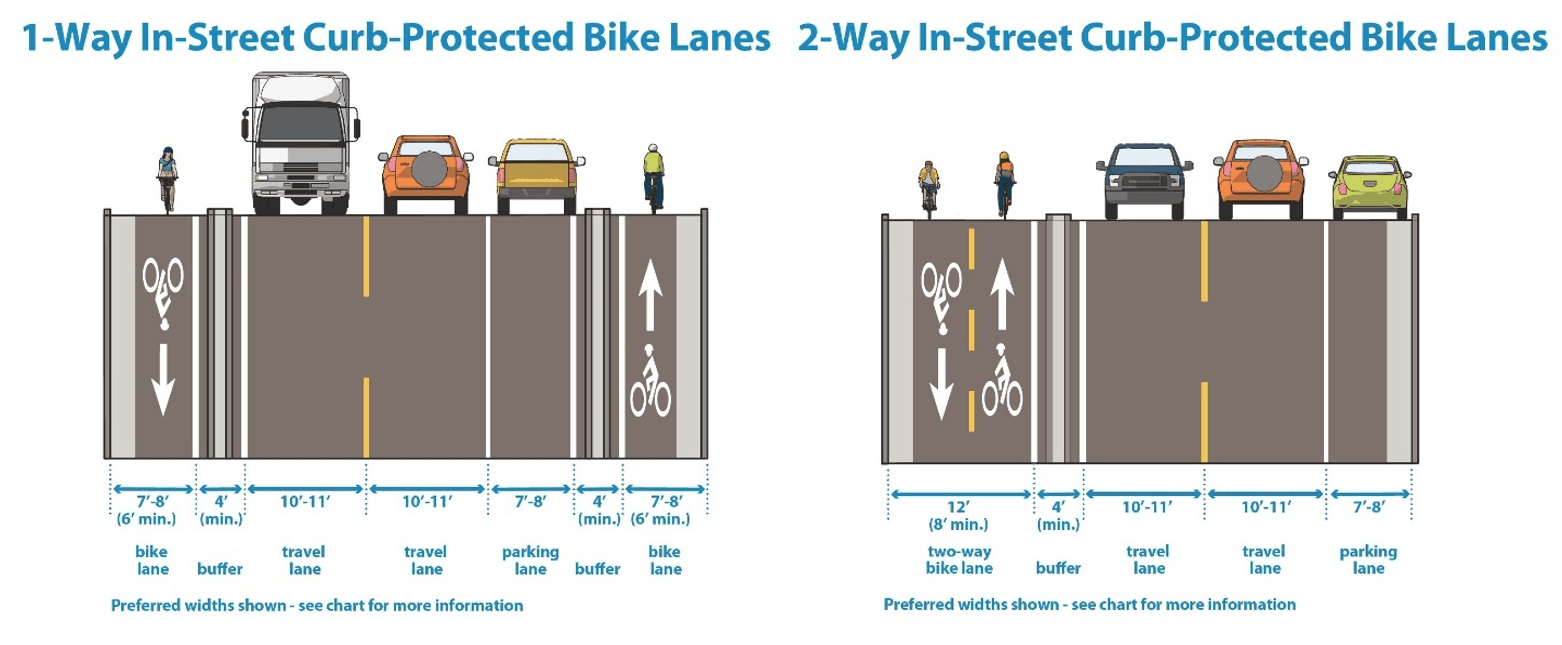

If a cycle track along a roadside is preferred, then communities need to decide if the bikeway will be a one-way or a two-way. Two-way cycle tracks are typically implemented on one-way streets. This provides broader access for those riding bikes to community destinations and limits the need to travel out of the way to get to the partnering one-way road. It does come with the disadvantage that drivers, as well as pedestrians, don’t always expect cyclists traveling in the opposite direction of vehicle traffic on one-way roads. Determining which option is best for the community requires looking into the project’s context, while factoring in safety.

Image Credit: City of Minneapolis (3.4E In-street curb-protected bike lanes :: Minneapolis Street Guide (minneapolismn.gov)

Cycle tracks along roadways also contain vertical separation to keep cyclists safe from vehicles. These vertical separations can include different curb types, planter boxes, or grassy buffers (medians, trees, etc.).

Cody Christianson, transportation project manager at Bolton & Menk, mentioned “most residents feel comfortable biking on residential streets, but it’s still crucial to know how to be a good pedestrian and a good driver, especially with the increasing number of cyclists out and about.”

Inclusive Biking in Action: Midwest Success

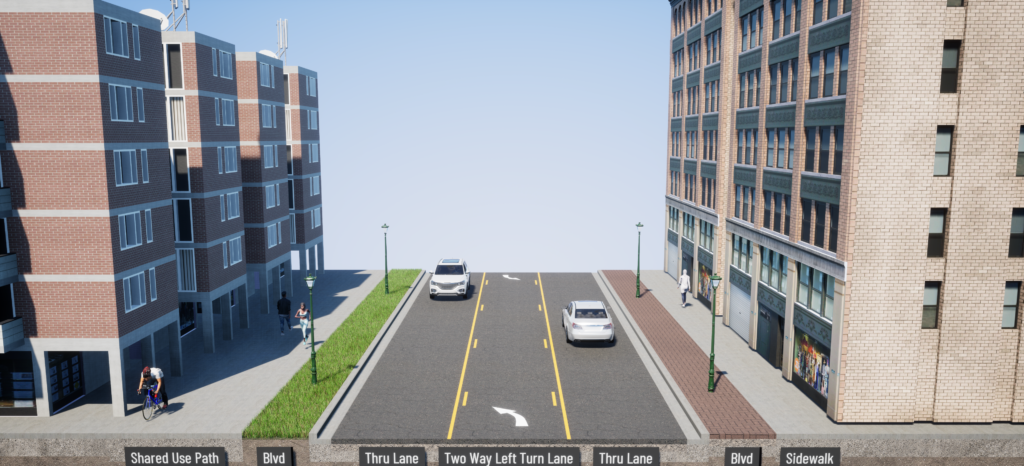

Rice Street, in the City of Saint Paul, Minnesota, started with an existing undivided 4-lane roadway, with no bike infrastructure and narrow pedestrian facilities. Rice Street serves a diverse mix of travel modes, and with some of the worst crash indexes in the state, safety was a huge focus in improving the roadway.

The community was asked how they needed the roadway to best serve them. Taking the 4-lane roadway to a 3-lane roadway was the obvious solution, but what was the best way to utilize the new open space?

The main consensus based on the community’s feedback was to feel safe on the road and when crossing the street. There was a push for adding bike facilities to the corridor as it’s a prime connection from the north end of Saint Paul into downtown; it is difficult to cross and was not included on the county or city bike plans when the project started. Rice Street is also one of the few bridge crossings of the BNSF Railway tracks.

After gathering initial feedback, a proposed option was a shared use path (biking/pedestrians together) on one side and a sidewalk on the other. The initial reaction within the design team was the shared use path wouldn’t work well in the community. Cody wanted to see that project option through, so it was kept as one of the options. “We took the community’s feedback into account and mixed those ideas with our expertise on different facility options. With this knowledge, we were able to recommend the best option for them and explain how it would benefit their constituents,” he stated.

County and city officials supported the shared use path and sidewalk design, and the idea became a huge success among the residents. The shared use path allows for more sidewalk space, landscaping, and parking flexibility. This shared-use design will allow families to walk and ride side-by-side, creating more of a community connection than a commuter bikeway. Even though the shared use path is not lightning fast, it will meet the needs for residents to get around comfortably and safely in their neighborhood. Construction of the Rice Street project will begin in 2024.

Inclusive Biking in Action: Southeast Success

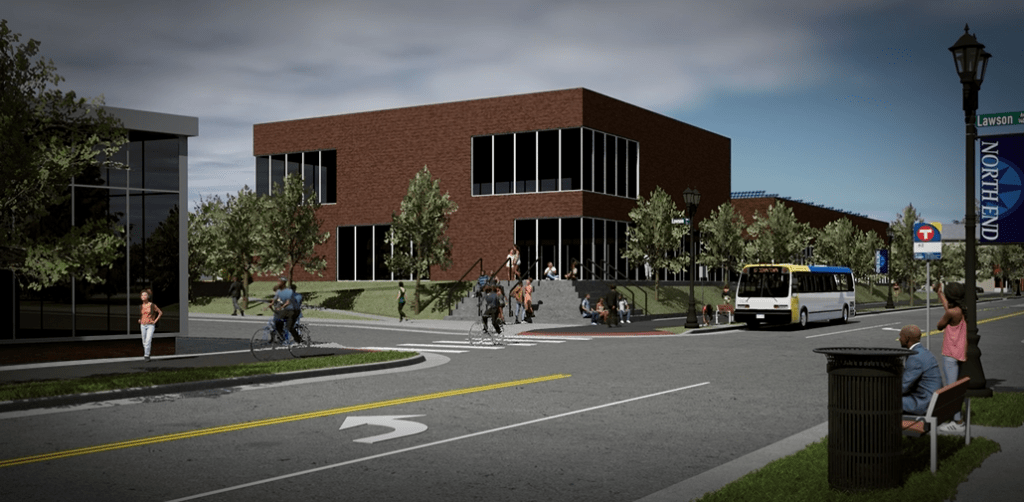

The West Sugar Creek Road RAISE Grant is a funding opportunity for implementing recommendations of the City of Charlotte’s Corridors of Opportunity initiative, which strategically invests in historically disadvantaged census tracts and areas of persistent poverty. Improving safety and comfort for vulnerable roadway users (people walking, biking, and taking transit) is the primary purpose of the proposed projects in the grant application. The grant will fund corridor improvements for walking, biking, and transit access that were recommended in previous corridor planning efforts, including broad public outreach and engagement and co-creation of a shared vision and strategies with stakeholders.

If awarded, the grant will fund three technology-driven mobility hubs to connect residents to flexible on-demand transit options, high frequency bus routes, and light rail. It will also include the construction of pedestrian and bike safety and access improvements, including two pedestrian hybrid beacon crossings, sidewalk gap connections, and a multiuse path. Through a partnership with Duke Energy, the multiuse path will include pedestrian-scale smart lighting and the mobility hubs will include electric charging for e-bikes, scooters, and electric vehicles.

The RAISE grant puts safety for vulnerable roadway users at the forefront. Between 2017-2022, there were 58 pedestrian crashes and 10 bicycle crashes, including 31 fatal or serious injury crashes on the 2-mile corridor. The city and Bolton & Menk calculated the proposed bike and pedestrian improvements could reduce enough crashes to save one life every 3.4 years and prevent 6 serious injuries per year.

These safety improvements will enhance resident connections to employment, services, retail, neighborhoods, parks, a major light rail station, and the 26-mile Cross-Charlotte Trail. This initiative will connect community members within an area of persistent poverty to jobs and services through safe, reliable, affordable, and sustainable transportation alternatives.

Abby Williams, transportation design engineer, shared “This project was very rewarding because we were able to calculate things like carbon emissions saved by switching travel modes from cars to bikes, and the public health benefit of providing a path for people to walk. It was a departure from black and white engineering.”

When transitioning away from a car-dependent lifestyle, people are often left with the first mile/last mile dilemma. If a destination is more than a couple of miles away, it is impractical for most people to bike. If public transit is an option, users need to find a way to get from their front door to the bus stop. Bicycles can provide an affordable mode of travel to complement the transit network, creating what we call a multimodal system. Both the Rice Street and Sugar Creek Road projects are Transit Oriented Development (TOD) projects, where multiuse paths complement the transit system by providing safe access and ‘first and last mile’ transportation.

Get Out There and Ride!

By building bikeable communities, commutes can become safe, sustainable, and enjoyable for everyone. Gathering community feedback, analyzing statistical data, and securing the right funding helps create safe and equitable bike-friendly infrastructure solutions for all users. As a resident in your own community, focusing on travel modes besides cars, such as bikes, e-bikes, and even walking, improves the health of yourself and the environment, while opening doors to a more social commute. Your commutes can become an adventure by riding to work on a weekday or exploring biking trails with family and friends on the weekend. The first step is to dust off your bike, fill up those deflated tires, and get out into the community. After all, it’s easy, just like riding a bike.

Looking to get involved in your biking community? Learn how to stay safe when biking: Bike Safety – National Safety Council (nsc.org)

Cody Christianson, PE, ENV SP, began his career in transportation engineering in 2008. He has expertise in roadway engineering and design, bike and pedestrian planning and design, and sustainability. Cody has national bicycle and pedestrian expertise that helps build support for improved multimodal infrastructure. By listening to community input, coordinating with project stakeholders, and using his industry experience, Cody designs improvements that create an inviting environment, enhance pedestrian and bicycle safety, and address community goals.

Abby Williams, EIT, is a transportation design engineer who began her career in 2017. She is responsible for designing and planning transportation projects that keep our communities moving safely and sustainably. Abby is experienced in bicycle, pedestrian, greenway, and roadway design, planning, and traffic analysis. Her passion for the field stems from her commitment to expanding active transportation offerings and minimizing environmental impacts to support public health and foster social equity.